How V8 JavaScript Engine Transforms Your Code: From Human-Readable to Machine Code

After you complete this article, you will have a solid understanding of:

- How JavaScript code is transformed from human-readable syntax into machine code via the V8 JavaScript Engine

- What is the Ignition Interpreter

- What bytecode is and how the Ignition Interpreter executes it using register operations

- What optimization techniques does V8 use

In this blog, we will do a high-level walkthrough of basically everything that happens going from our human-friendly JavaScript file all the way down to something computers can understand. We will focus on what happens on the browser side, and also on the V8 side. (V8 is a JavaScript engine used in browsers like Chrome, and also in Node.js.)

Let's start from the very beginning. Let's say we have a website called www.example.com and that website has this HTML file that contains a script called "script.js".

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

...

<script src="script.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

</body>

</html>

Script Loading

First, we type www.example.com into our browser. Then, the server sends the HTML file to us. After that, our browser uses something called HTML Parser to analyze what's in this HTML file that we got from the server.

The HTML parser is a fundamental component that browsers use to process web page code. It's basically the mechanism that reads the HTML code and transforms it into a meaningful structure while the web page is loading.

Note: If you're curious about how the server sends data to the client when we make a request, I have a very detailed blog post where we dive deep into this concept and more: How Data Travels the World to Reach Your Screen: A Deep Dive into OSI, TCP/UDP, HTTP, and More. While it's not necessary for this article, it will give you a good overview of the request-response cycle.

While the HTML Parser analyzes our code, it will encounter our script tag and will try to fetch the script.js file from either the network or maybe the cache. Either way, when it fetches the script file, a stream of bytes will be returned. Before the V8 engine processes the JavaScript code, the browser needs to convert these raw bytes into meaningful text data. And that's where the Byte Stream Decoder comes into play.

Byte Stream Decoding

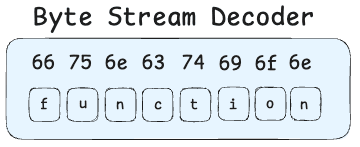

Our Byte Stream Decoder now has some bytes and it needs to convert these bytes to meaningful text that will be used in the next stages. In other words, it has to generate tokens based on the bytes it received.

See image below:

It basically converts bytes to letters based on its encoding system, and when it sees the function word, it generates a token and says something like "oh, I know this word is a keyword in JavaScript". It will do the same thing for all the bytes it receives. And finally, it will have generated tokens like this:

Parser

As the Byte Stream Decoder generates these tokens, it also sends all of them to another player that comes to the scene called Parser. A parser is a component built into the browser. Its job is basically to:

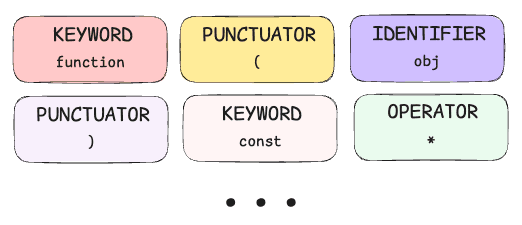

Take tokens from the Byte Stream Decoder and turn them into a meaningful hierarchical structure, such as an abstract syntax tree (AST).

This abstract syntax tree, created by the Parser, will represent our program. Let's see a very simplified version of an abstract syntax tree:

Also, parser will check for syntax errors while creating this tree. Because tokens themselves might be valid but they may not match certain syntax rules.

So far, we did tokenization with our decoder, and then we did parsing with those tokens.

Ignition Interpreter

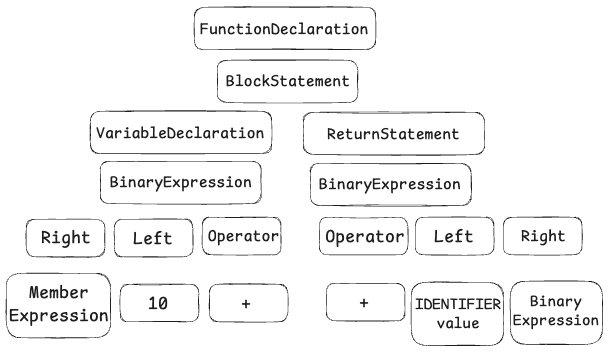

Finally, it's time for the JavaScript engine to do its work. This Abstract syntax tree is now sent to something called Ignition Interpreter. The Ignition Interpreter is a component within the V8 JavaScript engine. This Interpreter's most important mission is generating the bytecode based on the Abstract Syntax Tree it received.

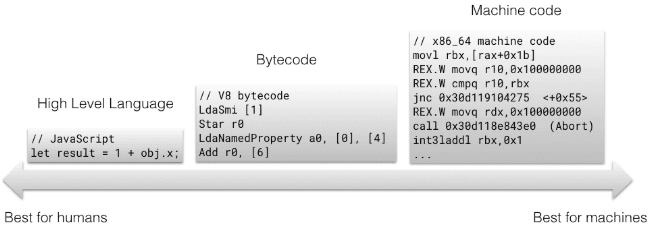

Bytecodes are abstractions of machine codes. Think of them as something in between the code we can read and the code machines execute. However, bytecodes are machine agnostic, which means that bytecodes can be compiled into whatever machine architecture you're running on. However, compiling bytecode to machine code is way easier if you generate bytecode which was designed with the same computational model as the underlying CPU.

And actually, this bytecode doesn't have to be a magical thing to us. We can actually see the bytecode that gets generated and understand it very well, which we will do right now!

Now, create a file called script.js, and write this function inside of it:

function calc(obj) {

const value = 10 + obj.x;

return value + obj.y + obj.z;

}

calc({ x: 2, y: 3, z: 4 });

If you want to see the bytecode that will be generated, open your terminal and execute:

node --print-bytecode script.js

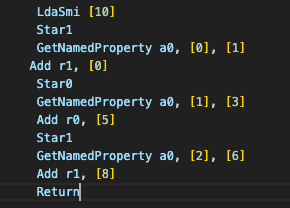

Now, you will see all the beauty of that bytecode! I hope it won't scare you because we will actually be interested in these parts specifically for right now:

We will look at the first photo, which shows the operations in bytecode, in more detail shortly.

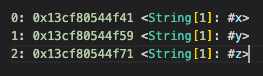

For the second photo, these string references in the bytecode show how the JavaScript engine stores property names (x, y, z) used in our object.

When the JavaScript engine processes your code, it stores object property names as strings. At the bytecode level, when you access obj.x, obj.y, and obj.z, the engine represents these names as string literals. The reason for this:

- In JavaScript, all object keys (except symbols) are stored internally as strings or symbols.

- At the bytecode level, when accessing obj.x, the engine first uses the "x" string literal to look up this property.

- That's why you see these string literals at the beginning of your bytecode.

But the important thing you need to know (that we will use in our bytecode) is that x is stored in index 0, y is stored in index 1, and z is stored in index 2. When we access these properties, their index number is necessary for us.

Before we dive deep into what's happening in the first photo, there's one more thing you should know.

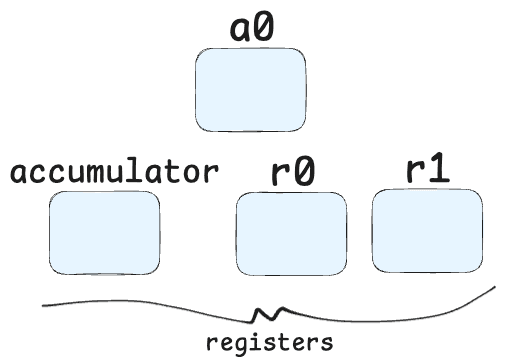

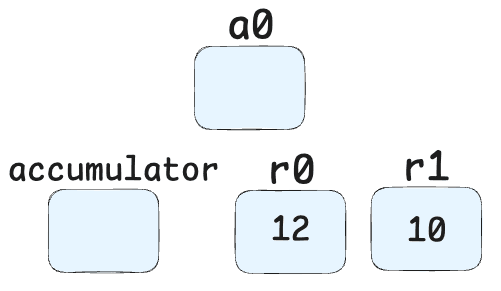

So first of all, Ignition uses registers in order to execute bytecode. There are registers like r0, r1, a0. And there is also an accumulator register that the bytecode uses for input and output.

Note: A register is a small, fast storage location built directly into the processor that temporarily holds data during code execution. In JavaScript's bytecode interpreter, registers are memory locations that store values being actively used in calculations, allowing the engine to efficiently access and manipulate data without repeatedly accessing the slower main memory.

r0, r1, r2, ... registers (General Purpose Registers):

- These are general purpose registers.

- They can temporarily hold any type of value (number, string, object reference, etc.).

- Used to store intermediate values during operations.

- The interpreter uses these registers for calculations, variable assignments, and various operations.

a0, a1, a2, ... registers (Argument Registers):

- They hold parameters passed to functions.

- a0 represents the first parameter, a1 the second parameter, a2 the third parameter, etc.

accumulator register:

- Can be thought of as the JavaScript VM's "working register".

- Used as input and output for most operations.

- Many bytecode instructions produce a value in the accumulator.

- The next operation typically uses the value in the accumulator.

- Primary location where result values are temporarily stored.

If they didn't mean anything to you, don't worry at all. Below, you will understand everything clearly. As you go through the steps, you can go back here and understand what registers are actually used for. It will give you a better understanding.

Now, let's go through the bytecode line by line to understand what each one means.

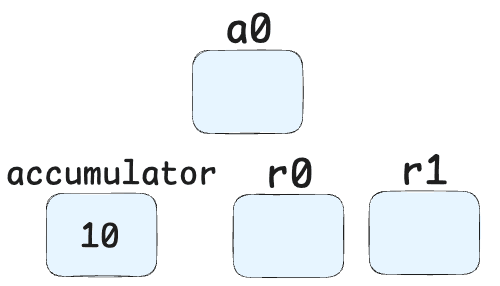

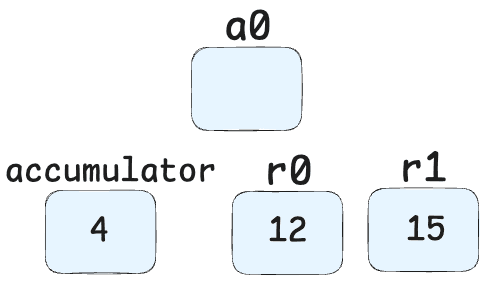

LdaSmi [10]-> This line means "Load Small Integer" - Loads the value 10 into the accumulator register. So our registers now look like:

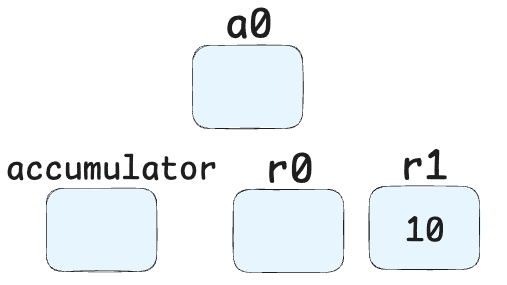

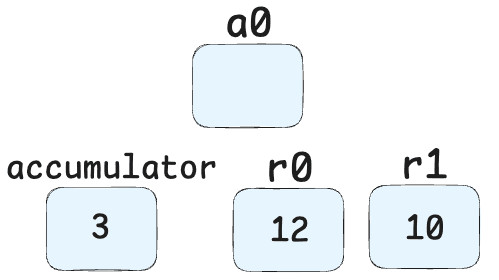

Star1-> This means "Store Accumulator in Register 1" - Stores the value 10 into register r1. Now it looks like:

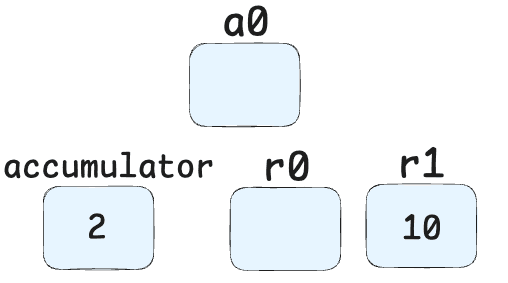

GetNamedProperty a0, [0], [1]-> Retrieves a property from object a0 (the parameter object) at index 0 (which corresponds to the "x" property). (Nevermind the [1] for right now.)

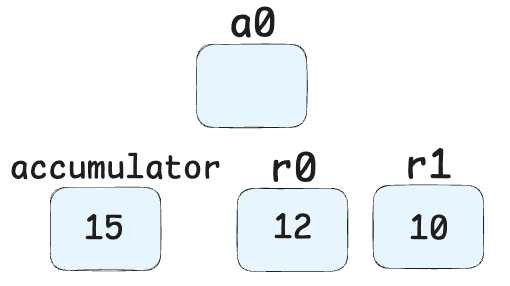

Add r1, [0]-> Adds the value in register r1 (10) to the current accumulator value (which is obj.x). Result: 10 + obj.x

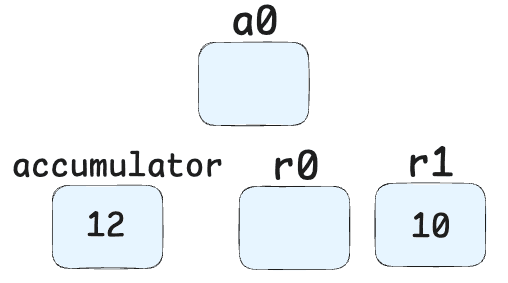

Star0-> Stores this result in register r0.

GetNamedProperty a0, [1], [3]-> Retrieves the property at index 1 from object a0 (the "y" property). (And again, nevermind the [3] for right now.)

Add r0, [5]-> Adds the value in register r0 (10 + obj.x) to the current accumulator value (obj.y). Result: (10 + obj.x) + obj.y

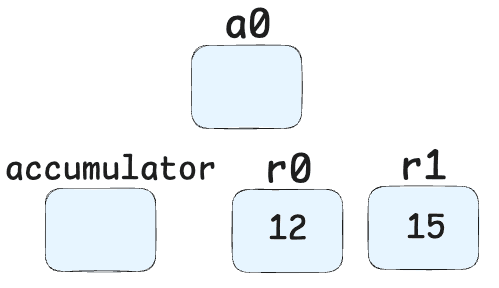

Star1-> Stores this result in register r1.

GetNamedProperty a0, [2], [6]-> Retrieves the property at index 2 from object a0 (the "z" property).

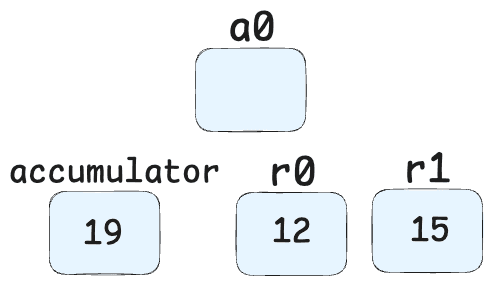

Add r1, [8]-> Adds the value in register r1 (10 + obj.x + obj.y) to the current accumulator value (obj.z). Result: (10 + obj.x + obj.y) + obj.z

Return-> Returns the final result from the function. (returns the current value of the accumulator register which is 19.)

So our code's bytecode equivalent is:

function calc(obj) {

const value = 10 + obj.x; // LdaSmi [10], Star1, GetNamedProperty a0, [0], [1], Add r1, [0], Star0

return value + obj.y + obj.z; // GetNamedProperty a0, [1], [3], Add r0, [5], Star1, GetNamedProperty a0, [2], [6], Add r1, [8], Return

}

Note: I've never shown the a0 register in the images to avoid any more confusion. But like we said at the beginning, the a register will hold parameters passed to functions. So actually when we say

GetNamedProperty a0, the accumulator will take those parameter values from the a registers.

Now, let's go back to the part that I told you to nevermind for right now. As you see in the bytecode:

GetNamedProperty a0, [0], [1]

We also use "[1]" while accessing this a0 register's first index. What's with this [1]? Or when we say accumulator's register, sometimes we said [0] or [5] to specify the accumulator's current values. Obviously, these values inside square brackets are not the values of those registers.

These values are called Feedback Vector Indices and they're part of V8's optimization technique. These indices are used in different places when optimizing the code. For example:

- Feedback vectors collect runtime type information during initial interpretation.

- V8 uses these vectors to decide when a function is "hot" (frequently called and type-stable).

- When a function meets certain heuristics (like monomorphic calls), V8 triggers JIT (Just-in-time) compilation to optimize it into fast machine code.

- If the type assumptions later become invalid (e.g., a different object shape appears), V8 may deoptimize and revert to interpreted bytecode.

Note: What is an

object shape? When we pass an object to V8, such as{x:2,y:3,z:4}, it creates ashapefor this specific object. You can think of theseshapesas basically just the structure of our object. These shapes are used for different optimization techniques behind the scenes.

So, JIT sits after feedback collection, it uses that feedback to decide what to compile and how to optimize it.

To complete our journey through V8, after the Ignition interpreter executes the bytecode, functions that are frequently called (becoming "hot") are identified through feedback vectors that collect runtime type information. When these functions meet certain criteria like stable types, V8's TurboFan optimizer compiles the bytecode into highly efficient machine code designed specifically for your CPU architecture. This JIT (Just-In-Time) compilation process transforms our JavaScript into machine code - finally something that our computers can understand directly.

This pipeline from human-readable JavaScript to raw machine instructions is what gives modern browsers their remarkable performance while maintaining the flexibility and developer experience we've come to expect from the web.

Was this blog helpful for you? If so,